SCIENCE EPISODE

GLP-1: Science and Hacks You MUST Know

So, science is always discovering these really cool little things that we can do to naturally increase our GLP-1, and what I want you to take away from this episode today is that, if you are on one of these medications, really look into your protein intake, lift weights, make sure you're not losing too much muscle mass, and then, for everybody else, learn all of these hacks that are going to help us keep our satiety levels higher so we can feel better and have fewer cravings.

Hello angels and welcome to the Glucose Goddess Show! I'm so happy that you're here. My name is Jessie Chespe. I'm a biochemist, and I'm obsessed with making science fun and easy to understand for all of us.

Today we're going to talk about a very hot topic: GLP-1 drugs. You may have heard of them — they have become very popular.

About one in every eight people in the US have tried one of these, from people with diabetes to celebrities. Originally they were used as type 2 diabetes medications, and now they're used mostly as weight-loss drugs. I wanted to talk about them because, when I dove into the science, I found some really fascinating things that these drugs have to teach us, and those fascinating things have to do with satiety, how eating in different ways can make us feel differently, how they're connected to glucose, and basically that we have a lot of cool stuff to learn from them. I'm excited to deep-dive into this topic today.

Think about the last time you had a really big meal, and then your aunt Sophie says, “Hey, Jessie, have another slice of pumpkin pie,” and you're like, “No, Aunt Sophie, I literally cannot eat anything else anymore, I'm so full.” You know the feeling? That is the feeling of satiety, and it's a really important feeling because it tells us that we've eaten enough; it's a very natural feeling. Now, these GLP-1 drugs target specifically that feeling of satiety and increase it in our bodies, so let's deep-dive scientifically into what's actually going on in your body to make you feel this feeling of satiety.

Let me go over to my computer to show you something. We have these little cells in our body called L cells; the complicated name for them is enteroendocrine cells. They're lining your gut, stomach, and intestine; they're just hanging out there, and they sense when you've eaten food. These cells in your digestive tract sense when food has come down from your mouth into your intestines and into your gut, and in response to you eating, they produce a molecule called GLP-1, which is what we're talking about today. Whatever you eat — pasta, a chicken salad, noodles, applesauce — these cells feel it and release GLP-1. The real fancy scientific name of this molecule is “glucagon-like peptide-1,” but we just call it GLP-1. Here's the deal: GLP-1 is responsible for reducing your appetite. GLP-1 tells different parts of your body that you've eaten enough — that you don't need another slice of pecan pie, another big bowl of chocolate mousse, or another pot of chocolate ice cream. Basically, GLP-1 is here to tell you that you can stop eating, and this is very important, of course.

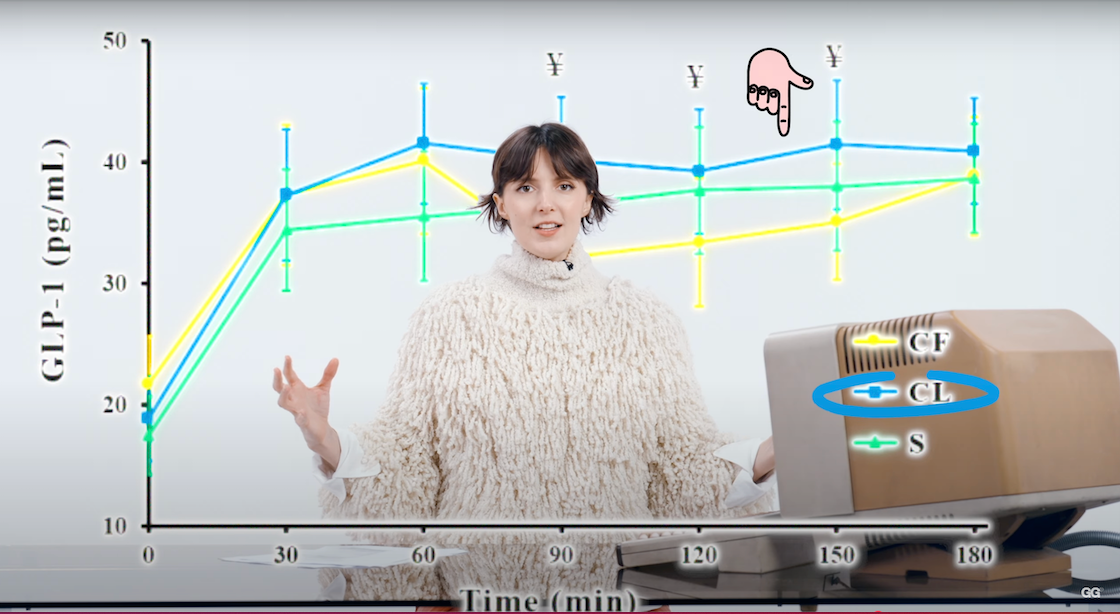

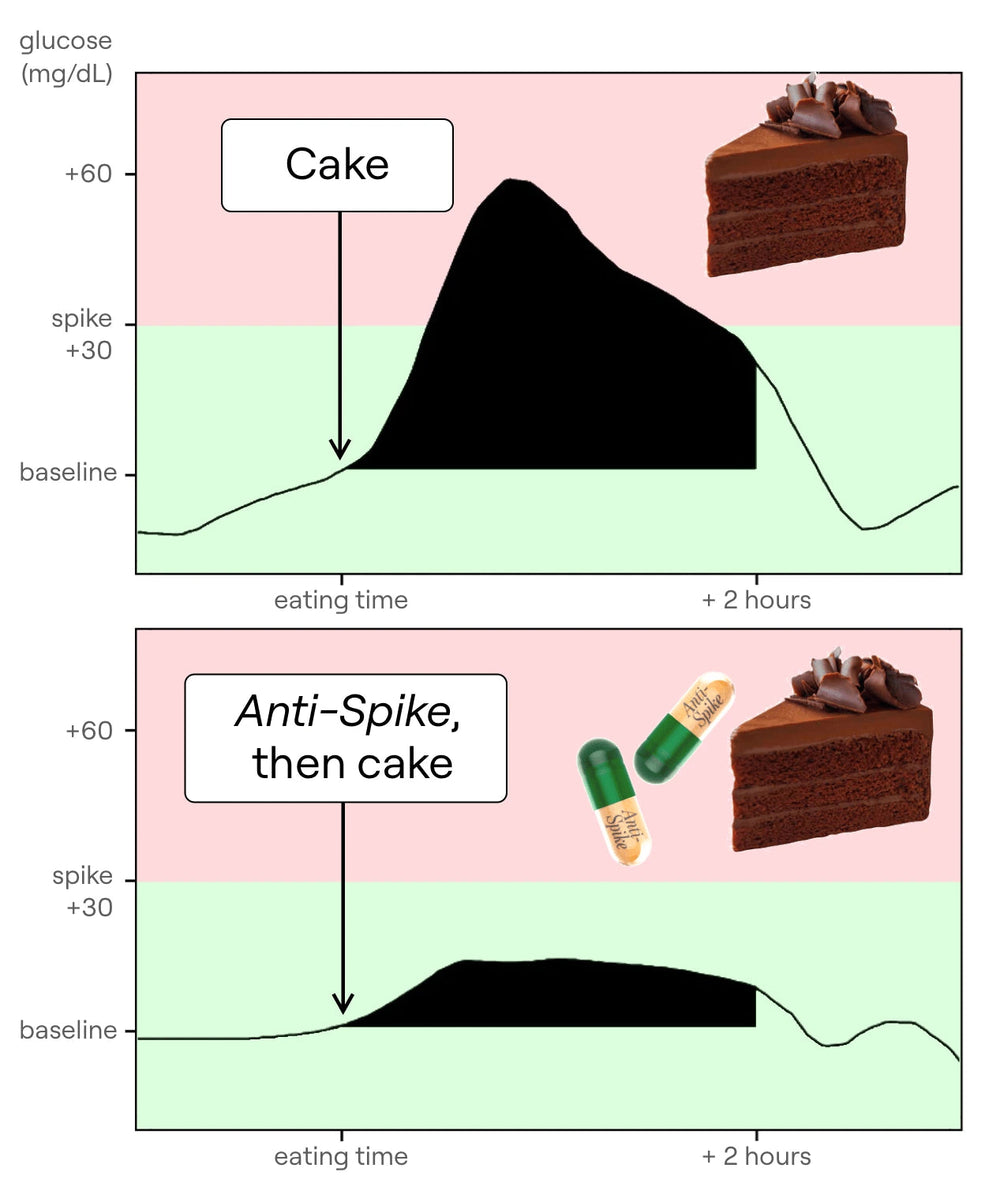

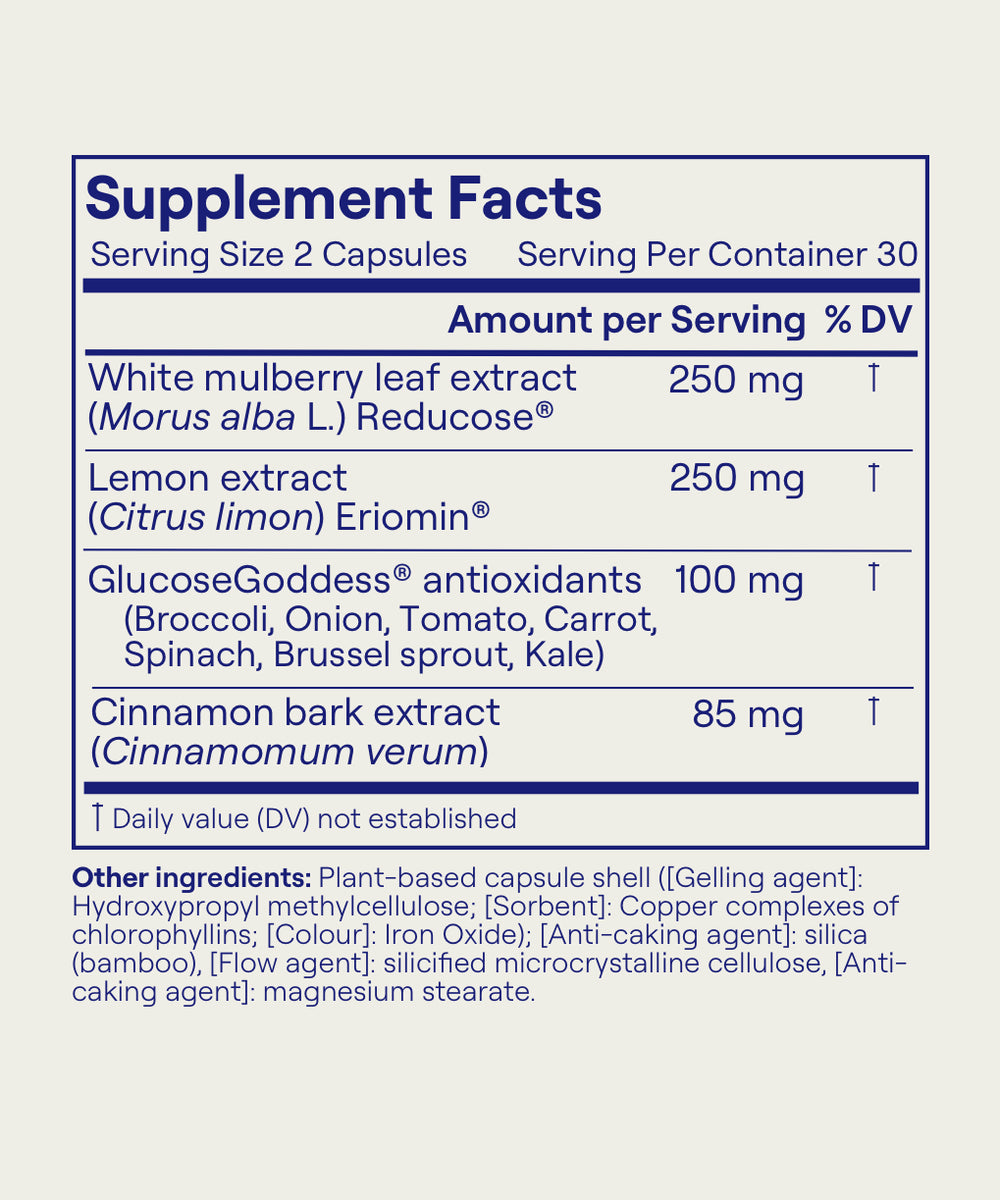

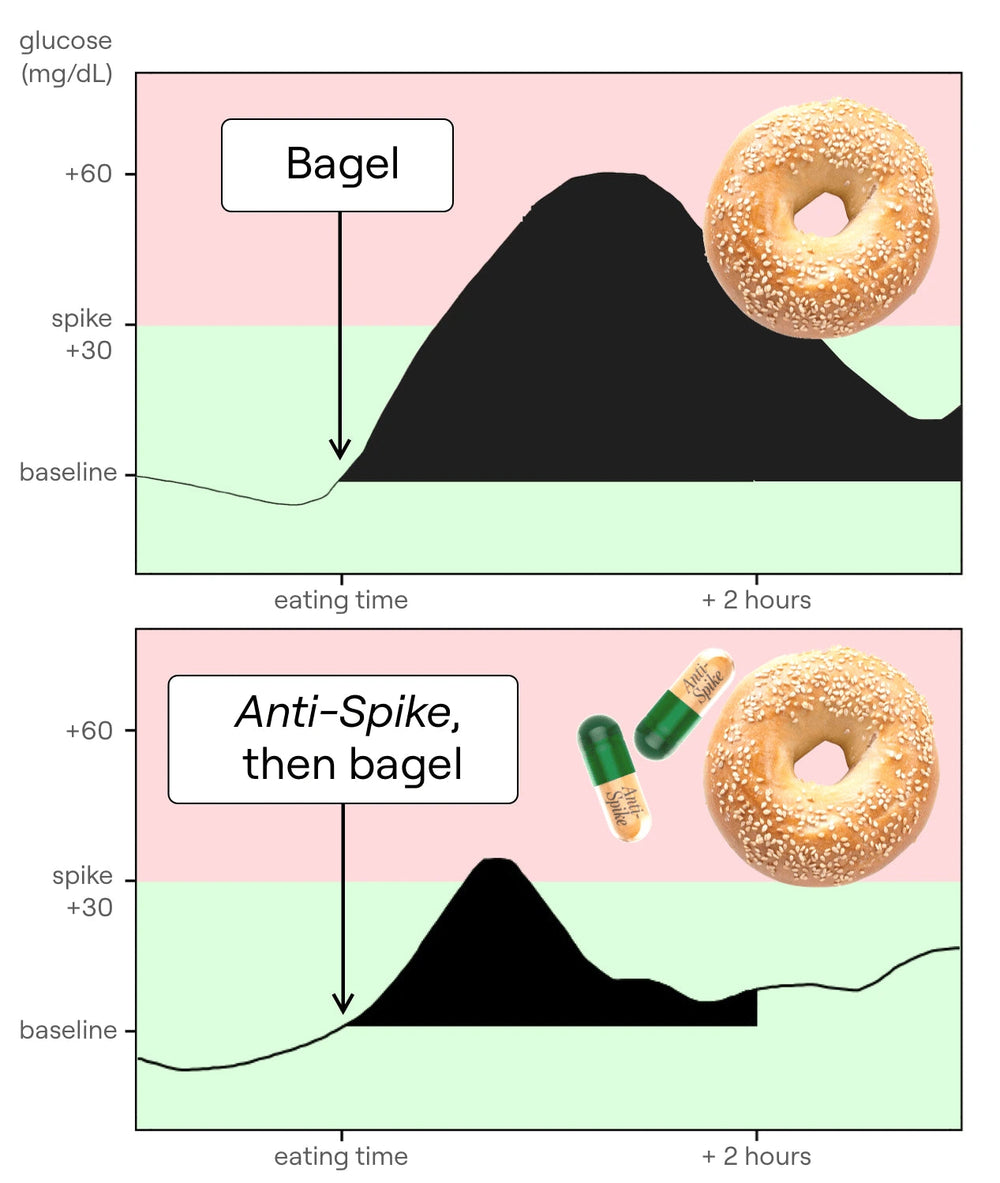

Time for a quick break to tell you about the supplement I have developed, Anti-Spike Formula. In my years of research, I've understood one key thing: keeping our glucose levels steady is the foundation of physical and mental health — no question. If I could only take one supplement for the rest of my life to help me reduce my glucose spikes and keep my glucose levels steady, it would be Anti-Spike Formula. I created Anti-Spike with two really powerful natural plant molecules. The first one is mulberry leaf extract. In a review of 12 randomized clinical trials on over 600 people, scientists found that mulberry leaf extract significantly reduces our glucose spikes after a meal by up to 40%, significantly reduces our insulin spike after a meal by up to 40%, and reduces fasting glucose levels by 8 mg/dL after just two months. This molecule reduces the absorption of glucose in our bloodstream; it slows down how quickly starches turn to glucose, therefore creating a massive reduction in the glucose spike of a meal. The second main molecule in Anti-Spike Formula is a molecule from lemon called eriocitrin. It's the molecule that makes lemons yellow and also has a really cool effect on our gut: it helps our gut produce more GLP-1. Clinical trials show that GLP-1 production increases by 17% after just two months of taking it; more GLP-1 means healthier glucose levels. I take two capsules of Anti-Spike Formula every single day before the meal of my day highest in carbs and sugars. Go to antispike.com to see all the science behind these ingredients, to see testimonials from thousands of people who've tried it, and to order your own Anti-Spike Formula bottle and try it for yourself.

GLP-1 works in a few ways: it slows down how quickly food moves from your stomach into your intestine, and it also distends your stomach — increases its size — which makes you feel full. Another thing GLP-1 does is signal to your hypothalamus — a little gland above the roof of your mouth connected to your brain. GLP-1 tells your hypothalamus that you've eaten enough, and boom: your brain gets the message that there's plenty of food down there and it doesn't need to tell you to eat anymore. What's really interesting, and got me fired up about this science, is that it's not just about how much you eat; the way that you eat is going to produce more or less GLP-1 — more on that later.

If you can't wait and want to download the hacks right now, they're in the description of this video: hacks to increase GLP-1 naturally.

Normally at rest, you always have a little bit of GLP-1 circulating in your body, and after you eat this amount doubles or triples. Scientists have done a lot of research to see how quickly after a meal the peak of GLP-1 happens; it's about 45 to 60 minutes after eating that GLP-1 increases, and then it comes back down — at that point you may start to feel a bit hungrier again. It's a cycle, really just a curve: you eat, GLP-1 increases, and over time it comes back down. This is normal — a natural part of human biology. These new drugs didn't invent GLP-1; GLP-1 has always been around and has always been part of a well-functioning body and brain.

Another important thing GLP-1 does is help your body deal with carbs — bread, pasta, rice, potatoes, anything sweet from a banana to a cake. GLP-1 also tells your body, “Hey, there are carbs in here; we need to manage them,” and, to manage those carbs, GLP-1 helps your body secrete insulin, the hormone that takes excess carbs and puts them away into storage — part of a normal functioning metabolism. This is where it gets really interesting. Scientists at pharma companies thought: GLP-1 is interesting; what would happen if we gave somebody a huge amount of GLP-1 artificially, either through an injection or a pill? They tested this. The first impact they saw was that these medications helped people with type 2 diabetes reduce their glucose levels — GLP-1 helps put away extra glucose — and that was the primary use. But a side effect they discovered was the complete obliteration of hunger. When you give your body a very high dose of GLP-1, you're simply not hungry anymore because GLP-1 cuts appetite completely; you're constantly in a state where your body thinks you just had a massive meal. This is what has made these drugs really popular: people are turning to them to suppress hunger.

There's a question I haven't been able to answer in my research: by how much exactly do these drugs increase GLP-1, and specifically how much more do they activate GLP-1 receptors? Some are GLP-1 agonists, some are GLP-1 analogs, but I couldn't find the answer online or in studies. For example, in humans our fasting normal concentration of total GLP-1 is typically 5–10 pmol/L and can increase up to ~40 pmol/L in response to a meal; with these drugs those numbers are much higher, but I haven't found the exact number — if anybody knows, please comment. Meanwhile, we're in a situation where these drugs are, in a way, necessary because of the toxic food landscape we live in. People are taking drugs to completely zap their appetite so they don't get tempted to eat the food around them, because that food is making them sick. Imagine if the water in our taps were so toxic that pharma companies had to create a drug to make us not thirsty so we wouldn't drink the water — that's kind of what's happening with these medications. The food is making us sick and giving us type 2 diabetes, so people are taking these drugs to not eat that toxic food. We lose sight of how we got here in the first place: the food we eat today is not healthy. Most of us are consuming ultra-processed foods with many refined carbohydrates and sugars, and those are making us sick. There is an appeal of these drugs for people with type 2 diabetes in particular, because there's a belief that type 2 diabetes cannot be reversed and you need medication — that's not true. If you're able and have the capacity and budget to change what you're eating, you can reverse type 2 diabetes with food, and that's what my hacks teach (link in the description if you want those hacks).

Let's discuss side effects. Are there side effects? Yes — and I want to make sure people know about a key one. People are taking these drugs now for weight loss; they don't have diabetes, they just want to lose weight. These medications don't just make you lose fat: they cut hunger, and you lose tissue from everywhere — not just fat mass but also muscle mass. This will happen with any diet if you drastically reduce how much you eat. Studies say up to 30% of the weight lost comes from muscle. You might feel like you don't care, but you should, because once you stop these medications, if you gain the weight back — which happens in many, maybe most, cases — one study shows that one year after withdrawal, participants regained two-thirds of their prior weight loss; on average people regain 2/3 of what they lost, and the weight you gain back is pure fat. You might end up having lost a lot of muscle and then regaining fat — not healthy. We need muscle for longevity, to stay healthy, to help our metabolism, to ward off disease. So if you or someone you know is on one of these drugs, it's key to maintain muscle mass: lift weights (yes, females too) three times a week — heavy — and, most importantly, eat enough protein. Most of us are under-proteined. We need about one gram of protein per pound of body weight per day — more than you think. If you're 150 pounds, you should eat ~150 g/day; one egg is not even 8 g, so you need the equivalent of around 20 eggs a day to maintain and build muscle. If you want more info on protein, there's a PDF in the description to calculate how much you need each day and a table of common foods and their protein content. I highly recommend — whether or not you're on these medications — looking at this, because it's key to feeling amazing and aging in good health. You guys know I've been doing my glucose hacks religiously; they are the foundation of my dietary habits. Adding the molecules in Anti-Spike has allowed me to get to the next level in a few areas: bloating (I feel so much better), energy levels (super consistent, “eagle energy” all day), and cravings for sugar (I love sugar, but Anti-Spike has given me a superpower over cravings). I know these natural molecules will help my long-term fasting glucose and fasting insulin levels, which is key to physical and mental health and healthy aging. Go to antispike.com to see the science, testimonials from thousands of people who’ve tried it, and to order your own Anti-Spike Formula bottle.

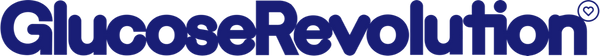

Now, natural ways to increase GLP-1 are actually super interesting. Who doesn't want to naturally feel fuller longer and have healthier glucose levels? The first thing to do is eat your food in the right order — a key hack to manage glucose levels — and scientific studies show it also helps increase GLP-1 production by up to 38%. You can increase GLP-1 produced by your little L cells by up to 38% simply by eating in the right order. In your stomach, if during a meal you eat in the wrong order — all your carbs first (bread, pasta, rice, potatoes, sugars) — the glucose in those carbs arrives in your bloodstream very quickly, causing a big glucose spike and a smaller GLP-1 release. If you eat in the right order — veggies first (very key), then proteins and fats, and last your carbs (starches like pasta and rice, then sugars) — the glucose from those carbs arrives much more slowly because it's being slowed by the foods already there; eating fiber first and protein next also increases GLP-1 production by up to 38%. As shown on a study graph, with the same meal composition, carbs-first yields less GLP-1 and carbs-last yields more. Public service announcement: eating in the right order, when it's easy, helps manage glucose and reduces constant hunger via more GLP-1 — and that GLP-1 also helps put away excess glucose more quickly, reducing spikes. When you can, do it — but don't stress. If you're having a mixed dish, don't worry; a simple way is to add a small plate of veggies at the start of your meal.

Another hack: chewing. When you chew your food — instead of drinking it or swallowing it whole — you release more GLP-1. In the supplement world, a cool option to increase GLP-1 naturally is a special molecule from lemons — eriocitrin — a powerful antioxidant that, if you get enough of it, increases naturally produced GLP-1 by up to 17% after three months; the highest quality is in my Anti-Spike supplements (link in the description).

Another hack concerns what we eat: for a long time scientists believed carbs would increase GLP-1 the most, but the jury is still out. What we do know is that adding protein to a mixed meal increases GLP-1, and a specific amino acid seems to increase GLP-1 the most (based on a rat study): phenylalanine. Top foods containing this include beef, chicken breast, pork chops, tofu, tuna, pinto beans, milk, squash and pumpkin seeds, pasta, and sweet potatoes.

Finally, there’s a very common South American drink called yerba mate (from Argentina), a high-caffeine drink made with fermented tea leaves; this increases GLP-1 as well. Science is always discovering cool little things we can do to naturally increase GLP-1.

What I want you to take away today is: if you are on these medications, look into your protein intake, lift weights, and make sure you're not losing too much muscle mass; for everybody else, learn the hacks that help keep satiety higher so we can feel better and have fewer cravings.

Check the description of this episode for a PDF with natural hacks to increase GLP-1 levels. I've learned so much about this cool little molecule, and I hope you feel like you know a bit more about it too today.

Thank you so much — I will see you next time; see you in the next episode.

Anti-Spike Supplement

Anti-Spike Supplement

The Recipe Club

The Recipe Club

Course

Course

50 Breakfast Recipes

50 Breakfast Recipes

50 Veggie Starter Recipes

50 Veggie Starter Recipes

20 Vegan Recipes

20 Vegan Recipes

20 Gluten-Free Recipes

20 Gluten-Free Recipes

The 10 Glucose Hacks

The 10 Glucose Hacks

Vinegar

Vinegar

Alcohol

Alcohol

Fasting

Fasting

GLP-1

GLP-1

What to Eat Before & After Exercise

What to Eat Before & After Exercise

Protein

Protein

PCOS

PCOS

Menopause

Menopause

My MRI Story

My MRI Story

Breakfast

Breakfast

Supplements

Supplements

Clothes on Carbs

Clothes on Carbs

Eggs & Cholesterol

Eggs & Cholesterol

Chocolate

Chocolate

Food Labels

Food Labels

Veggie Starters

Veggie Starters

Move After Eating

Move After Eating

Why Glucose Matters

Why Glucose Matters

Glucose Revolution

Glucose Revolution

The Glucose Goddess Method

The Glucose Goddess Method

9 Months That Count Forever

9 Months That Count Forever