SCIENCE EPISODE

When it comes to blood sugar, not all supplements are created equal.

Many popular options claim to help balance glucose levels. But do they actually work?

I’ll walk you through the science-backed reasons why I don’t take certain common supplements, and introduce you to the two natural plant molecules I do take every single day to support my glucose levels, reduce spikes, and feel my best.

Why managing glucose spikes is so important

Glucose spikes (those sharp rises in blood sugar after a meal) can lead to short-term symptoms like cravings, fatigue, brain fog, and even long-term health issues like inflammation, hormone imbalance, prediabetes, diabetes and heart disease. That’s why keeping glucose levels steady is one of the most effective things we can do for our physical and mental well-being.

I always say: food comes first. My 10 Glucose Hacks are the foundation.

But if you're looking for an extra layer of support from supplements, here's what works, and what doesn’t.

FREE RESOURCE

The Glucose Hacks

Instantly download the hacks as a 1-page printable PDF.

Popular glucose supplements I don’t take (and why)

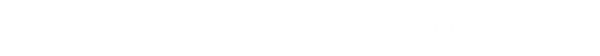

1. Vinegar capsules & vinegar gummies

While a tablespoon of liquid vinegar before meals can reduce glucose spikes by up to 30%, vinegar capsules and gummies don’t seem to work.

A study comparing the liquid and capsule forms found that vinegar capsules did not have a significant effect on glucose spikes and did not improve insulin resistance. On the contrary, the capsules may even worsen it. (read study)

What about vinegar gummies? They often contain added sugar, which defeats the purpose entirely.

Verdict: Liquid vinegar works. Capsules and gummies are not worth it.

FREE RESOURCE

My vinegar mocktail recipes

Instantly download two vinegar recipes for free.

2. Fiber Pills

Fiber is amazing for glucose control when it comes from whole foods like vegetables. So theoretically yes fiber pills could reduce the glucose spike of a meal. But in reality:

- You would need 6 to 10 fiber pills before meals to blunt the glucose spike. For example, you’d need 6 capsules of psyllium husk before a meal to get the same amount of fiber as in 1 cup of broccoli.

- They’re often impractical, and may cause bloating or discomfort.

Verdict: Whole veggies are better. Pills are inefficient and can lead to digestive discomfort.

3. Bitter melon

Despite its popularity, studies on bitter melon show minimal effects on blood sugar levels.

- One meta-analysis showed no significant improvement in HbA1C or fasting glucose. (ready study)

- Another found a drop of only 0.3% in HbA1C, really not enough to justify daily use. (read study)

Verdict: Slight benefits, but not powerful enough for daily use.

4. Berberine

Berberine is well-known for its blood sugar-lowering effects. Here’s how it works:

- There is a molecule in our cells called AMPK. Its job is to sense when your cells are running low on energy, and it tells your body to burn more glucose to make energy.

- Supplementing with berberine activates this AMPK molecule, which leads to more consumption of glucose.

- The result: Your body starts using up more glucose. After supplementing daily with berberine for 2 months, studies show a lowering of fasting glucose levels and reduced insulin resistance (read study).

The advantages of berberine are that it’s cheap and it works: it’s proven to reduce fasting glucose levels and insulin resistance after 2 months at a dose of 2 grams daily.

The drawbacks of berberine:

- You have to take high daily doses (about 2 grams per day, so 5 to 8 pills per day).

- You have to be very patient to see an effect. Only after 2 months of 2 grams daily will you notice anything.

- It has no impact on your meals’ glucose spikes.

- The high dose required could potentially cause side effects. Whether it’s completely safe is still debated among health agencies (ANSES, EFSA).

Verdict: Works, but inconvenient and slow. There’s a better option.

The two natural molecules I do take every day

After years of research, I found two plant molecules that truly work. They’re both backed by high-quality clinical studies, they have immediate and long-term effects, and they’ve made a noticeable difference in how I feel after meals: fewer cravings, better energy, and steadier glucose levels.

These two molecules are:

- DNJ from mulberry leaf extract

- Eriocitrin from lemon peel extract

Let’s dive into the science behind each one.

Anti-Spike Formula

1. Mulberry leaf extract: reduces glucose spikes by up to 40%

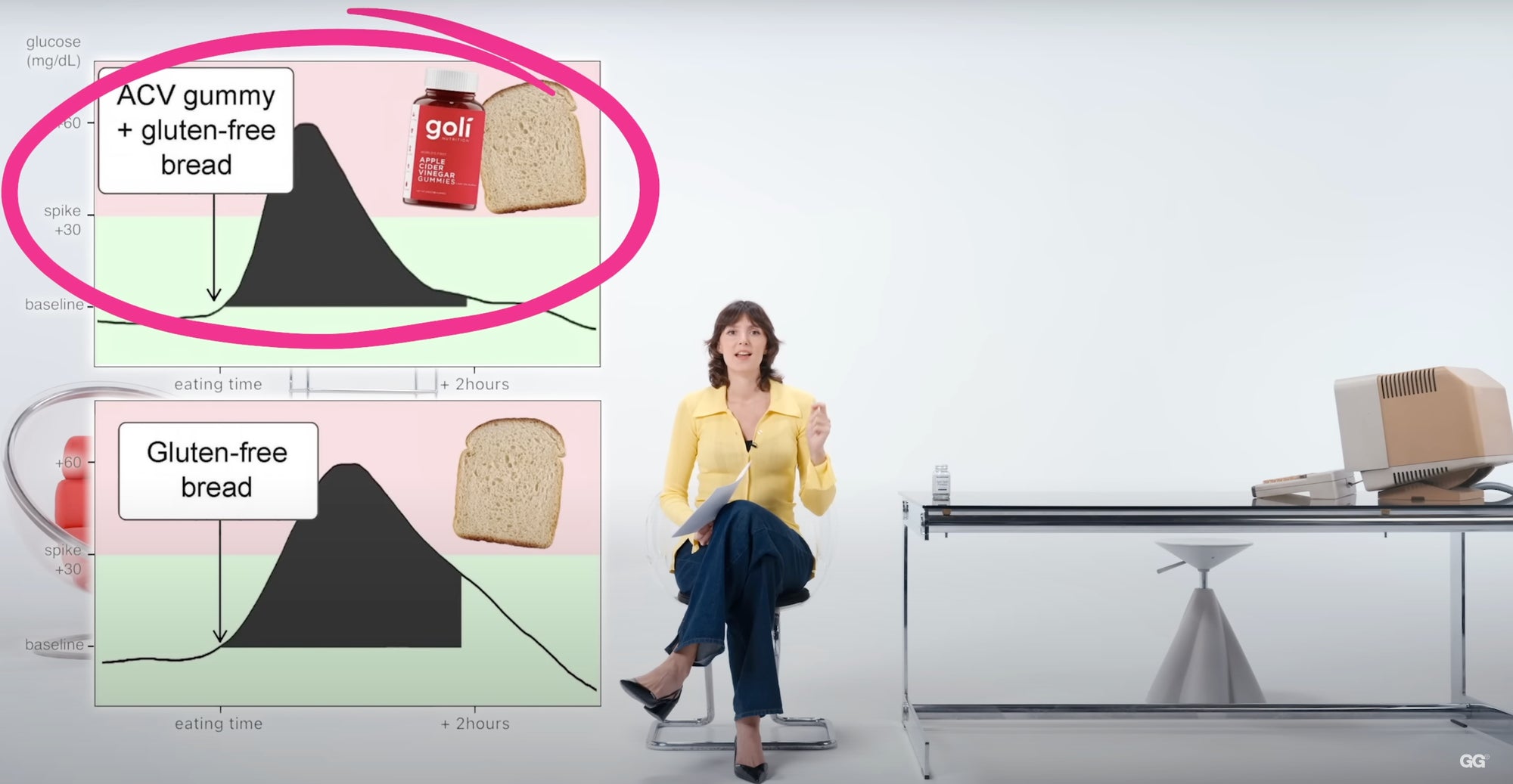

Mulberry leaf extract comes from the leaves of the mulberry tree and contains a powerful compound called DNJ (1-deoxynojirimycin). DNJ inhibits an enzyme called alpha-glucosidase, which is responsible for breaking down carbs into glucose in your digestive system.

What happens when DNJ slows this process down?

- You absorb carbs more slowly.

- You get a flatter glucose curve after eating.

- You avoid the cycle of glucose spike → insulin spike → energy crash.

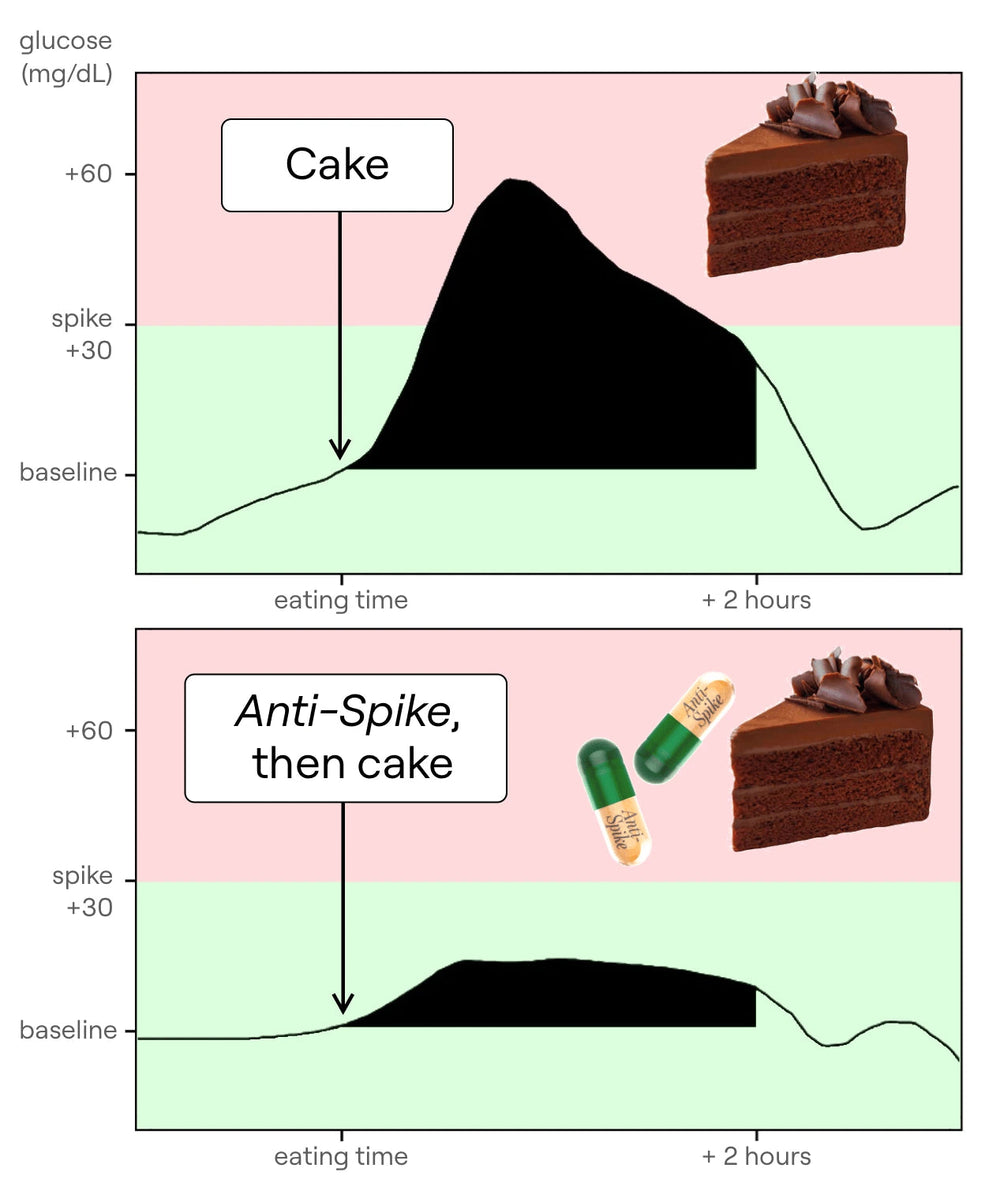

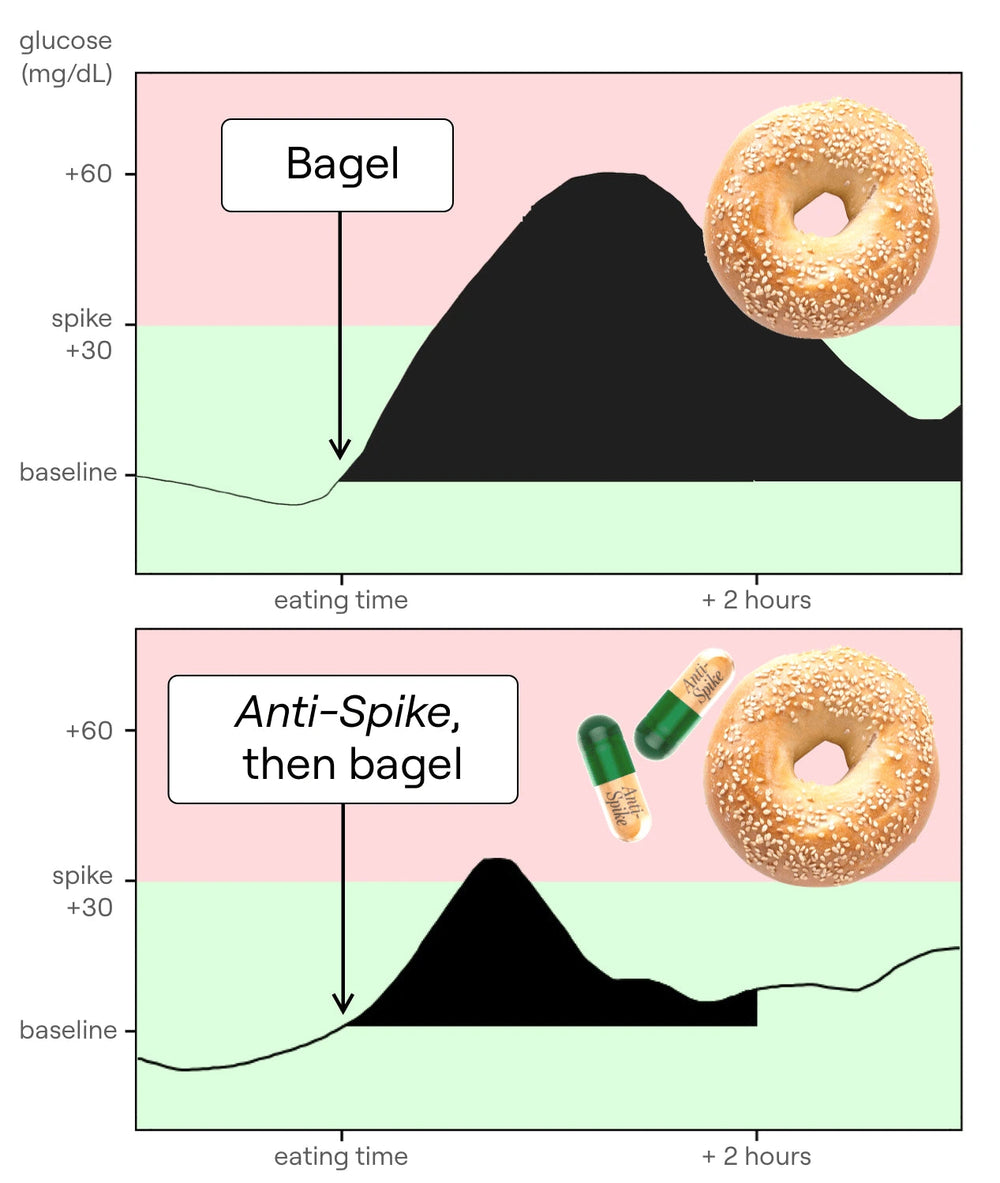

A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study tested 250 mg of mulberry leaf extract before a meal and found a 40% reduction in the post-meal glucose and insulin spikes (read study).

That’s a dramatic result, not only for blood sugar but also for reducing cravings and energy dips after eating.

Another study, a systematic review and meta-analysis of 12 randomized controlled trials with over 600 participants (read study), showed that daily use of mulberry leaf extract led to:

- A significant drop in fasting glucose

- A reduction in HbA1c (a marker of long-term glucose control)

- A measurable improvement in fasting insulin sensitivity

Why I take it: It works immediately when taken before meals and also supports better metabolic health over time. I take 250 mg of high-quality extract right before my highest-carb meal each day.

2. Lemon Polyphenol (Eriocitrin): Boosts GLP-1 and Regulates Blood Sugar

The second molecule I take is eriocitrin, a natural polyphenol found in lemon peel. It’s what gives lemons their vibrant yellow color, and it does much more than that.

Eriocitrin has been shown to increase the body’s production of GLP-1, a hormone secreted by your gut when you eat. GLP-1 plays a vital role in:

- Reducing appetite

- Slowing gastric emptying

- Enhancing insulin secretion

- Improving blood sugar reduction

In a recent crossover randomized clinical trial, participants who took 200 mg of eriocitrin daily for 3 months had a 22% increase in GLP-1 production (read study).

But perhaps the most exciting finding came from a study on people with prediabetes: 24% of participants reversed their condition entirely (meaning their fasting glucose dropped back to healthy levels) after just 3 months of eriocitrin supplementation (read study).

Eriocitrin also has anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, which further support overall metabolic health.

Why I take it: It acts via a completely different pathway from mulberry leaf, and it supports long-term glucose control, appetite regulation, and even fat metabolism. It’s a perfect complement to DNJ.

Anti-Spike Formula

Anti-Spike Formula: my daily glucose supplement

I didn’t start out as someone who wanted to create a supplement. Honestly, I’ve always leaned food-first, and minimal when it comes to pills. But when I started seeing the evidence for DNJ from mulberry leaf and eriocitrin from lemon extract, I got really excited.

This wasn’t marketing. This was data. Multiple randomized controlled trials, meta-analyses, dose-specific results — all pointing to real, measurable effects on blood sugar.

I tested both of these ingredients individually. I noticed a drop in my post-meal spikes. I felt fewer cravings. My energy stayed more stable. My "sugar crashes" were basically gone.

So I asked myself: What if we combined these molecules? At the exact doses used in clinical trials? What if we created a formula that:

- Works immediately: reduces the glucose spike of the very next meal.

- Supports long-term health: improves fasting glucose, insulin sensitivity, and cravings over time.

- Is natural, safe, and low-effort: just a couple of capsules a day.

- And most importantly: is scientifically backed at the right clinical doses, not under-dosed or hype-driven.

And so that’s exactly what I built.

What's inside Anti-Spike?

- 250 mg Mulberry Leaf Extract (DNJ)

The same dose used in trials showing up to 40% reductions in post-meal glucose spikes (read study), and improved long-term fasting glucose and HbA1c (read study).

- 250 mg Lemon Extract (Eriocitrin)

Shown to increase GLP-1 levels by 22% (read study), support appetite regulation, and even reverse prediabetes in 24% of cases (read study).

- Cinnamon Extract (1 g equivalent)

A highly potent extract of ceylon cinnamon, another plant with tons of evidence supporting its effect on fasting glucose over time (read study).

- Veggie Antioxidants

To boost cellular health, support inflammation balance, and reflect the antioxidant power of the glucose hacks I teach.

How I Use Anti-Spike

I take two capsules a day, just before the meal that’s highest in carbs, which is often dinner. The effect is real: I don’t get that big spike → crash cycle anymore. I feel full for longer. And I’ve completely lost the urge to snack on sugar afterward, even when it’s around.

I still do my glucose hacks (like having a savoury breakfast, eating veggies first, moving after eating), but Anti-Spike gives me an extra layer of protection, and just makes life so much easier when I’m busy, traveling, or eating something I can’t fully control.

Anti-Spike Formula

The scientific studies mentioned in this episode

ANSES (French Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health & Safety). “Opinion of the French Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health & Safety on the Risks Associated with the Use of Food Supplements Containing Berberine.” (2019) www.anses.fr/en/system/files/NUT2018SA0095EN.pdf

Cesar T B et al., “Nutraceutical Eriocitrin (Eriomin) Reduces Hyperglycemia by Increasing Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 and Downregulates Systemic Inflammation: A Crossover-Randomized Clinical Trial.” Journal of medicinal food 25, no. 11 (2022): 1050-1058. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35796695/

Cesar T B et al., “Exploring the Association between Citrus Nutraceutical Eriocitrin and Metformin for Improving Pre-Diabetes in a Dynamic Microbiome Model.” Pharmaceuticals (Basel, Switzerland) 16, no. 5 (2023): 650. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37242433/

Chattopadhyay K et al., “Effectiveness and Safety of Ayurvedic Medicines in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Management: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Frontiers in pharmacology 13 (2022): 821810. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35754481/

Chen S et al., “Evaluation of mulberry leaves' hypoglycemic properties and hypoglycemic mechanisms.” Frontiers in pharmacology 14 (2023): 1045309. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37089923/

Cui W et al., “Effect of mulberry leaf or mulberry leaf extract on glycemic traits: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Food & Function 14, no. 3 (2023): 1277-1289. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36644880/

Ding F et al., “The impact of mulberry leaf extract at three different levels on reducing the glycemic index of white bread.” PloS one 18, no. 8 (2023): e0288911. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37561734/

European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). “Technical Report on the Safety of Berberine as a Food Supplement.” EFSA Supporting Publications (2023) https://efsa.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.2903/sp.efsa.2023.EN-8246

Feise N K and Johnston C S, “Commercial Vinegar Tablets Do Not Display the Same Physiological Benefits for Managing Postprandial Glucose Concentrations as Liquid Vinegar.” Journal of nutrition and metabolism 2020 (2020): 9098739. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33489366/

Khan A et al., “Cinnamon improves glucose and lipids of people with type 2 diabetes.” Diabetes care 26, no. 12 (2003): 3215-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14633804/

Lown M et al., “Mulberry-extract improves glucose tolerance and decreases insulin concentrations in normoglycaemic adults: Results of a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled study.” PloS one 12, no. 2 (2017): e0172239. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28225835/

Mohamed M et al., “A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Crossover Study to Evaluate Postprandial Glucometabolic Effects of Mulberry Leaf Extract, Vitamin D, Chromium, and Fiber in People with Type 2 Diabetes.” Diabetes therapy : research, treatment and education of diabetes and related disorders 14, no. 4 (2023): 749-766. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36855010/

Ramos F M M et al., “Lemon flavonoids nutraceutical (Eriomin®) attenuates prediabetes intestinal dysbiosis: A double-blind randomized controlled trial.” Food science & nutrition 11, no. 11 (2023): 7283-7295. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37970408/

Ribeiro C B et al., “Effectiveness of Eriomin® in managing hyperglycemia and reversal of prediabetes condition: A double-blind, randomized, controlled study.” Phytotherapy research : PTR 33, no. 7 (2019): 1921-1933. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31183921/

Thondre P S et al., “Mulberry leaf extract improves glycaemic response and insulaemic response to sucrose in healthy subjects: results of a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled study.” Nutrition & metabolism 18, no. 1 (2021): 41. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33858439/

Thondre P S et al., “Understanding the Impact of Different Doses of Reducose® Mulberry Leaf Extract on Blood Glucose and Insulin Responses after Eating a Complex Meal: Results from a Double-Blind, Randomised, Crossover Trial.” Nutrients 16, no. 11 (2024): 1670. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38892603/

Wang, Ruihua et al., “Mulberry leaf extract reduces the glycemic indexes of four common dietary carbohydrates.” Medicine 97, no. 34 (2018): e11996. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30142838/

Ye Y et al., “Efficacy and Safety of Berberine Alone for Several Metabolic Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials.” Frontiers in pharmacology 12 (2021): 653887. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33981233/

Yin R V et al., “The effect of bitter melon (Mormordica charantia) in patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Nutrition & diabetes 4,no. 12 (2014): e145. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25504465/